Historical trauma and mental health in Indigenous communities

September 22, 2020At Blue Cross, we are focused on achieving racial and health equity as a means of inspiring change, transforming care and improving the health of all. Specifically, we want to shed light on mental health, especially within BIPOC communities. This post is part of a series of in-depth conversations with members of our associate resource groups (ARGs) focused on mental health.

These discussions are intended to provide a safe space for associates to share their lived experiences and ideas on how the mental health needs, challenges and successes of BIPOC communities can be better addressed at all levels.

American Indians report experiencing serious psychological distress 2.5 times more than the general population and have the highest rates of suicide of any racial/ethnic group in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The facts speak or themselves:

Rates of substance abuse among American Indians are higher than those of the general U.S. population. American Indians have the highest rates of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, inhalant and hallucinogen use disorders compared to other ethnic groups.

Individuals who experience trauma or are incarcerated or homeless are more likely to need mental health care and addiction treatment. Indigenous peoples are disproportionately overrepresented in these vulnerable populations. When looking at statistics related to suicide, depression and addiction in Indigenous communities, we need to understand the root causes— trauma, racism, poverty and colonial violence. There cannot be a discussion of American Indian mental health without understanding historical trauma and how it continues to impact individuals and communities today.

Who are Indigenous peoples?

Indigenous peoples are those who descended from the original inhabitants of an area prior to colonization by settlers. Indigenous peoples belong to distinct cultural groups that existed long before modern states were created and current borders defined. Across the world, Indigenous peoples have retained unique cultural, social and political characteristics that are different from the dominant societies in which they live.

Indigenous peoples are those who descended from the original inhabitants of an area prior to colonization by settlers. Indigenous peoples belong to distinct cultural groups that existed long before modern states were created and current borders defined. Across the world, Indigenous peoples have retained unique cultural, social and political characteristics that are different from the dominant societies in which they live.

In the United States, Indigenous peoples are also known as American Indians or Native Americans. There are 574 federally recognized American Indian tribes in the U.S. Each tribe has their own unique customs, language, spirituality, government and identity.

Federally recognized tribes are sovereign nations and hold a government-to-government relationship with the United States. In exchange for land, the U.S. government holds a trust responsibility to American Indian tribes, guaranteed by treaty law, to provide for the health and welfare of American Indian people in perpetuity.

The CDC recognizes that the “disruption of indigenous persons’ relationships with their homelands, including land, language, culture and religious beliefs, has been suggested to be at the root of health disparities.”

Despite this sacred trust responsibility, there is a long history of federal policies that have violated treaty rights, led to a loss of land and lifeways and carried devastating consequences for American Indian people.

Forcible removal from ancestral homelands, poverty and generational trauma continue to impact physical and mental health of American Indian people today. The CDC recognizes that the “disruption of indigenous persons’ relationships with their homelands, including land, language, culture and religious beliefs, has been suggested to be at the root of health disparities.”

What is historical trauma?

Beginning in 1492, American Indian peoples have been subjected to extreme trauma, violence, destruction of cultural practices and oppression that carry lasting impacts across generations. The cumulative emotional trauma that has been passed from one generation to the next is what researchers call “historical trauma.”

Historical trauma “contributes to the current social pathology of high rates of suicide, homicide, domestic violence, child abuse, alcoholism and other social problems among American Indians.”

In her research, Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart (Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota) found historical trauma “contributes to the current social pathology of high rates of suicide, homicide, domestic violence, child abuse, alcoholism and other social problems among American Indians.” Dr. Brave Heart observed similar features in response to other massive group trauma survivors, including Holocaust survivors and survivors of WWII Japanese internment camps, which she calls “trauma response.”

The trauma of Indian boarding school

Indian boarding school is just one of many sources of historical trauma. Indian boarding schools were designed to separate American Indian children from their families and forcibly assimilate them to white society. “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” was the motto the U.S. government used when they forced thousands of Native children to attend boarding schools across the nation.

In boarding schools, American Indian children were stripped of all connections to their culture. They were prohibited from speaking their language, wearing traditional clothing or practicing their spirituality. Violence and corporal punishment, along with physical, mental and sexual abuse were routinely used against children. This era lasted from 1860 to 1978.

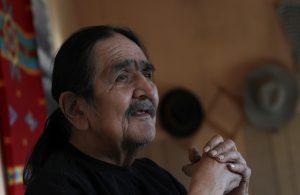

My own father is a boarding school survivor. I have seen firsthand how the trauma he experienced as a boy continues to dramatically impact his health today. My father went to Saint Augustine Indian Mission School on the Winnebago reservation in Nebraska. He was subject to brutal punishments, humiliation and assault. This led him to develop PTSD and unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as addiction.

My own father is a boarding school survivor. I have seen firsthand how the trauma he experienced as a boy continues to dramatically impact his health today. My father went to Saint Augustine Indian Mission School on the Winnebago reservation in Nebraska. He was subject to brutal punishments, humiliation and assault. This led him to develop PTSD and unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as addiction.

Boarding schools destroyed the mental health of generations of American Indians and robbed them of the ability to learn healthy family dynamics.

Attempts to eradicate Native culture, including the forced separation of Native children from parents in order to send them to boarding schools, have been associated with negative mental health consequences.” – Kleinfeld & Bloom

In order to examine the mental health needs of Indigenous peoples today, it is essential to understand the impact of U.S. government policies such as extermination, relocation, boarding school and forced assimilation.

Continuing barrier to mental health services today

American Indian face numerous barriers in accessing mental health services and treatment. For one, mental health and addiction recovery treatment are severely limited in remote reservation communities. In both urban areas and reservation communities, culturally competent mental health treatment is scarce.

Culturally based treatment models have been demonstrated to be most effective in addressing the needs of American Indians. However, the vast majority of mental health and addiction treatment services in the U.S. operate within a Western framework that is frequently at odds with an Indigenous world view.

Culturally based treatment models have been demonstrated to be most effective in addressing the needs of American Indians. However, the vast majority of mental health and addiction treatment services in the U.S. operate within a Western framework that is frequently at odds with an Indigenous world view.

To effectively meet the needs of American Indians and eliminate disparities in care, providers must work to increase cultural competency and ensure that treatment is relevant and sensitive to the needs of Indigenous communities.

American Indian community members hold the solutions to the challenges they face and should be at the forefront of work to create health equity in Tribal Nations and urban communities. We cannot address mental health concerns for American Indian people without addressing the root causes: systemic racism, historical trauma, generational poverty and unequal access to quality health care and treatment.

BIPOC mental health series

Read additional posts in this series

I am a boarding school survivor and a former tribal leader and also retired from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Office of the Special Trustee for American Indians.

I would like more information on HT on American Indians please.